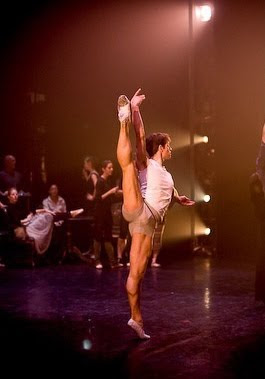

Diarmaid O'Meara - behind the dancer

Diarmaid O'Meara @ The Royal Opera House

Photograph : Mo Greig

Most of the expert dancers you see on stage have been through rigorous, repetitive training to become an elite athlete – because that’s what professional ballet dancers are. ‘Expertise’ is defined in a study

(1) in 1993 as ‘the result of intense practice for a minimum of ten years’. The study went on to describe the specific type of practice an expert needs to acquire this expertise as ‘deliberate practice’, which means getting the best instruction but also several hours of focused practice every day. What is missing from the study is that these ten years of deliberate practice must be completed before puberty, because of the very high level of flexibility needed.

Malcolm Gladwell, in Outliers

(2) explains that achievement is talent plus preparation, and that preparation almost always totals 10,000 hours. It’s not enough to practice for an hour a week for 10,000 weeks if you want to be an expert; the conclusion of the 1993 study - the requirement for ‘deliberate practice’ - is fundamental. An experiment in 1995

(3) concluded that it takes 180 practice trials for the human brain to consistently reproduce new, simple movement patterns. There is nothing simple about ballet choreography and you can see how a much longer training period becomes necessary.

That said, it’s not unheard of to start a vocational career in ballet at a later stage. Royal Ballet Principal dancer Johan Kobborg started his career with the Royal Danish Ballet School at the age of 16. Darcey Bussell had a lot of catching up to do in her first years at the Royal Ballet School and found it hard to pick up the steps. It’s been said that the classical Greek Philosopher Socrates learned to dance when he was 70 because he felt that an essential part of himself had been neglected.

But there’s late and then there’s meeting yourself coming backwards. I’m at the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden to talk to Diarmaid O’Meara, who started training at 22. That’s not a typo. He had never considered doing ballet, there were no family links and he didn’t start vocational training until he’d passed a degree in Genetics, started a PhD and had a job as a research assistant (researching arthritis). His heart wasn’t in it, “I just didn’t love it enough, and I need to really love something to do it”. The reality of being in a lab six days a week was not for him, “it was just something that I could never see myself doing as a career.”

When you meet him it’s easy to see why. He’s chatty, intelligent & attentive - our wobbly table was distracting me until he whipped out a notebook to steady the leg - not someone I can see in a white coat and those dodgy blue shoe-covers. He’s very open and will talk to anyone, but dig deeper and he’s wary at first; my guess is that he makes strong and loyal friendships, but only after taking his time to get to know you first. One of his friends, fellow professional dancer Megan Wood, with whom he is currently working, tells me “Diarmaid always puts a smile on my face. When our feet are hurting and we're exhausted, he will always make me chuckle! He is a very genuine and sincere person and his hugs are always the warmth of friendship. I definitely consider Diarmaid a true friend.”

So what alchemy can account for the professionally trained ballet dancer in front of me? In his native Ireland there is no vocational ballet training, and Diarmaid says “any Irish people that have gone anywhere in dance have had to leave and come to London. Or gone abroad to France or Russia”. Of ballet he says “I’d seen it on TV and I was a bit mesmerised by it, but because there wasn’t any dance presence, it was something you didn’t think about.” Diarmaid was “really involved in sports so that took up all my extra energy.” He modestly tells me that he “represented Ireland in decathlon at one stage”. The choreographer George Balanchine said “ I don't want people who want to dance, I want people who have to dance”, and I think this sentiment applies very much to Diarmaid.

Moving to Dublin proved to be the catalyst, and in typically understated fashion, just as in all success stories – think Carlos Acosta in the backstreets of Havana – cut to 10 years later and he’s centre stage at Covent Garden - "a friend of mine was doing a few dance classes and invited me to go along with her. I did some contemporary, some hip-hop and then I wandered into a ballet class one day.” The way he tells it, it’s almost impossible to imagine how transformative that class turned out to be. “It all happened pretty quickly from then. I started taking regular classes in Dublin, and one teacher I had, Stephen Brennan, said ‘if you want to make anything happen, you need to move to London’.” Diarmaid was taking five classes a week by this stage, but only for a few months – nothing like the ten years or more of his contemporaries.

He applied to Central School of Ballet “and luckily, Bruce Sansom was the director at the time, and he was very long-sighted. He thought that they could do something with me.” Given that Diarmaid had earlier told me “I had this idea in my head that it was too late : that ship had sailed, it was never going to happen”, what made him take the plunge and leave his job ? “I hedged my bets - something I love vs. something that merely paid the bills”.

Diarmaid O'Meara @ The Royal Opera House

Photograph : Mo Greig

Crucially, he has incredibly supportive parents, who, if they were worried, never voiced it. “They tell me now, that at the time when I said ’I want to go to London to Central School of Ballet and I want to be a dancer’, they were a bit like, ‘this is a bit hare-brained’. But at the time they were like, ‘if this is what you want to do, go for it. We’re behind you 100%'. They’re ultra-supportive, which made making a big decision like that so much easier, knowing that they were behind me.” Many studies have shown that parental support is one of the key drivers when it comes to opportunities to succeed.

The training was “really tough. In first year I discovered that I had really bad posture and I was really uncoordinated, and I just had to scrap everything and begin from scratch. I think because I had spent so many years not doing ballet, I really needed to just concentrate on the basics. At the beginning of the 3 years I didn’t really know what I wanted from it. I knew I wanted to perform but I didn’t really know what direction I wanted to go in, because I didn’t know if I was any good, or if I was any good, what area was I good at. But over the 3 years I realised that classical ballet was what I really absolutely loved.” In between training Diarmaid worked (and still does) at Sadlers Wells Theatre in Islington.

“The teacher I had in second year, Paul Lewis, was just phenomenal. I don’t think I would have got a ballet job if it wasn’t for him, because he really just pulled it out of me. He was really, really hard on us, on all of us, and he was really hard on me. But it totally paid off because he knew what he wanted to get out of us, and it was all for us, you know, he wasn’t hard on us just for the sake of being hard on us. He was hard on us because he wanted us to do really well. And I’ve huge respect for him because of that.”

Paul Lewis confirms the hard work but points to Diarmaid’s incredible work ethic and level-headed attitude towards his training, “Diarmaid came to us with having very, very little previous experience and we thought it was a bit of a long shot really, but he was very determined and so we gave him a chance at the school. I enjoyed having him around enormously, watching him overcome the challenges that the course presented. He took it all in his stride. He surpassed all our expectations really, he was incredibly focused. He was coming to this very late so he knew he had to knuckle down and really try and catch up, which he did, and he worked incredibly hard for his three years here. But he’s managed to change himself physically as well, because he’s a strong man anyway, but he looked more like a rugby player than a ballet dancer when he arrived, and he’s managed to completely change his physique.” I ask whether he had to adapt his teaching to accommodate Diarmaid’s late start but he says emphatically not, “the information was the same. It just meant that in terms of trying to change your body already when you are a fully formed man - it’s one thing when they’re younger and physically they’re still growing, they’re changing - Diarmaid was pretty much set. But he still managed, through stretching and just working his body using different muscles, really working very hard at it, he did manage to completely reshape himself. He had co-ordination issues and things which, a lot of it he managed to overcome. He’s still working on it, and I think for any dancer that’s always an on-going thing, you’re always striving to improve and he’s still going to do that but his work ethic was phenomenal."

Approaching Christmas in his first term of third year, recovering from an injury proved, as it does with many dancers, to be a pivotal time. Again, the understated way that he talks about breaking his foot in class, “I landed awkwardly on a patch of slippy floor, and my foot just cracked, and that knocked me out for 8 weeks”, belies how testing an injury can be, particularly in the important graduation year when dancers audition for professional work. “But when I got back from that, I came back way stronger than I’d been before. I literally started again with the basics, while my foot was healing.” A Cuban lady at the school looked after injured students and “she was all about finding connections in your body, all movements were very organic, using your breath. She did lots of visualisations. So I went into class every day with my foot up in a chair and I used to visualise myself doing each exercise. And I imagined how it would feel, what my posture was like, what my arms were doing, all the co-ordinations, and what muscles I would feel doing the exercises. So then when I came back I didn’t feel uncoordinated, everything felt right.”

Diarmaid O'Meara & Anna Blackwell in Ascent by Mikaela Polley

Photograph : Bill Cooper.

Diarmaid created several roles in his final year; two roles in Matthew Hart’s

Whodunnit and one part in Mikaela Polley’s

Ascent, which she describes as “a blend of classical ballet and contemporary dance” and “it starts in one place but by the end it’s very high energy.” Polley initially watched the whole year in a workshop, because her style was classical with a contemporary edge “so I was looking for dancers that could help me creatively create the piece, and who had that something a little bit different, who were willing to take some challenges and some risks.” The next step was to choose around 18 dancers with whom she wanted to work, and she included Diarmaid. “It was a cast of 6, but I had several casts because it’s important that the students have this opportunity to work with choreographers.”

Diarmaid’s broken foot was still healing at this point, but Polley remembers “he was always present, he was always there. He just wasn’t able to physically join in. I knew that I wanted him to do one of the roles and that there were multiple performances and that he would have that opportunity.” In fact he ended up dancing all of the performances in that role, “and taking it to the next level in the performance side of the piece, and he was fantastic. He’s a very clever man, he knew his work, he was prepared, and I think it gave him an opportunity and challenge to show what he was able of. I think the school were amazed because he came to dance so late, that he had this ability that shone through.”

With graduation fast approaching, Diarmaid auditioned when time allowed. He tells me of one audition in Poland which really tested his mettle. “I couldn’t make the actual audition date

(because of his performance schedule on tour with Central) so I said ‘can I come up and take company class ?’ Big mistake. There were about 70 dancers in the studio, and the class lasted less than an hour. It was just so fast, everything was in Polish, I could not pick up a single step, and back then, because I was nervous as well, not being able to pick up the steps, nobody helping me and the director watching me - I just looked like I’d walked in off the street and I’d never done a class in my life. That was just horrific. It was horrible.” It’s impossible to over-emphasise the strength of character Diarmaid demonstrates; graduating students have been through years of constant sifting and evaluation from their teachers, but one of the most challenging adaptations to company life is the reality of working for yourself.

Photograph : Bill Cooper

For the same reason he also missed an audition for Ballet Theatre UK, so he asked the Director and Choreographer of the company, Chris Moore, to watch him in class. Moore says “I was keen to offer Diarmaid a contract after seeing him in class at Central School due to his clean and well finished class work. As I was looking for a partner for Maria

(Engel, who dances the Sugar Plum Fairy), it was essential that I found someone who would bring a lot of character and style to the role of '

Nutcracker' as well as the right height and physique.”

Polley confirms this, “he’s an excellent partner. I could see very instantaneously that he was a very good partner and he was able to experiment and was very strong and could do some of the more difficult lifts, so I could specifically pinpoint him into a role which was great.”

Diarmaid O'Meara & Maria Engel in the Arabian Dance from Christopher Moore's The Nutcracker

Photograph : Mo Greig

Ballet Theatre UK began rehearsals this Autumn and I’ve watched them several times since. I can very clearly remember being impressed by Diarmaid’s ability to portray the characters in various roles even in the rehearsal studio; necessary here because the Company has ten dancers and two alternate casts. When I ask Moore about Diarmaid’s performances, he tells me, “Diarmaid has worked very hard in his characterisations and has great skill in switching from a 'classical prince' to other characters such as the Harlequin doll and the Butler. Diarmaid has also become very good at working on stages of various sizes while still staying true to the choreography and production.” A choreographers dream then.

Diarmaid O'Meara as The Prince & Maria Engel as Sugar Plum Fairy in Christopher Moore's The Nutcracker

Photograph : Mo Greig

The central pas de deux between the Sugar Plum Fairy and her Prince is famously tricky, “performing the pas de deux was actually really, really scary, because its ultra-classical, ultra-formal and then I’m responsible for Maria, for making her look fantastic, not that she needs any help, and thankfully I had good pas de deux training at school.” Back to Paul Lewis, “he’s a very good partner, being a strong lad is a huge asset. He’s a good looking guy.” How did Maria and Diarmaid form the trust they needed ? “Luckily when we met we just instantly had a rapport, so we were able to talk to each other, which made it very easy to get comfortable with it, so now the pas de deux is actually the most comfortable part of the ballet for me.”

I ask him what he’d like to dance and with whom, given the choice. “I’d love to do Balanchine, something like The Four Temperaments and Theme and Variations, I absolutely love it.” He also mentions Onegin and “if I was dancing something dramatic, it would have to be Laura Morera, she’s just so intense when she’s on stage. She’s just so passionate.”

I’ve watched several of Diarmaid’s performances and it’s true that he makes it look easy, which it isn’t. The company have been travelling all over the UK, and I wonder where he considers home now that he’s been away from Ireland for years, “where my loved ones are, lucky for me, that means many places.” Performing is what he loves, but he’s smart enough to start planning for the future, which may involve teaching “even now, if I see someone doing something wrong technically, I’ll give them a correction, and I like others to do this to me too”, and, as he already has a B.Sc. (Hons.), re-training as a Physiotherapist is a possibility, “I have already researched where and how much it will cost me”.

Diarmaid O'Meara as The Prince & Maria Engel as Sugar Plum Fairy in Christopher Moore's The Nutcracker

Photograph : Mo Greig

Polley wants to know whether I too encountered the force-field that is the charm of the Irish (I did), and adds, “I found him to be very intelligent. He was obviously slightly older than some of the other students but that maturity shone through in his professional approach to working, not only with me but within the company. He was always eager for feedback, and to improve, and I think that’s what will help him into his professional career, just to keep working hard. He’s got a very lovely nature about him, and I think that will stand him in good stead in the future. He’s got a nice presence on stage and he has some very nice attributes to him. He was a very delightful man to work with. I wish him well for the future.”

Lewis says “he’s doing really, really, really well. He needs to keep working as he is, because there is still room for improvement, he’s going to grow, but I’m very, very, very pleased with what Diarmaid has managed to achieve. I’m thrilled that he’s working now; he’s left the school and gone into employment and I’m sure there are going to be other opportunities for him as well after this. I think he’s going to have a very interesting future.”

Once the tour is over, he’ll be home for Christmas, and then the gruelling process of auditioning begins again (but don’t expect Diarmaid to make a drama out of it – after all, his favourite quote is ‘what’s for you won’t pass you by’), “I don’t know if I’d like to leave London, but if there’s a job outside London, there’s a job outside London.” I can’t imagine that London wants to lose him, so what does the future hold ? “I’ll just keep working and putting myself out there and the rest is for someone else to decide.”

References

1. The Role of Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance, K. Anders Ericsson, Ralf Th. Krampe, and Clemens Tesch-Römer, 1993

2. Outliers, Malcolm Galdwell, 2008

3. Relative phase alterations during bimanual skill acquisition. Journal of Motor Behavior, Lee,T. D., Swinnen, S. P., & Verschueren, S. (1995).

4. Hot House Kids, produced by Neil George, presented by Deborah Bull, BBC Radio 4

I would like to thank those who have contributed to the making of this interview – Paul Lewis, 2nd year men's teacher, Carol Been & Anya Clifton at Central School of Ballet, Steven Drew & Mikaela Polley at Rambert Dance Company, Christopher Moore at Ballet Theatre UK, Megan Wood, Mo Greig, Neil George at the BBC and Deborah Bull.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)